1. OVERVIEW

For family offices looking to build a VC investment programme, there are a few key considerations that they must bear in mind:

- VC is hard. Most VC-backed companies are unsuccessful and median VC fund returns are disappointing.

- VC is a power law industry. Just a handful of companies account for the majority of the eventual returns from each vintage year. These companies are typically backed by a concentrated group of the best VCs.

- Past performance is the best guide to future performance. Every VC firm has a compelling story for why they will be successful. But ultimately, the data doesn’t lie.

- The best companies take time to mature. VC fund performance in the first few years is not predictive of where a fund will eventually end up.

Understanding these factors in detail is essential to building a successful VC programme.

2. VC IS HARD (BUT NOT IMPOSSIBLE)

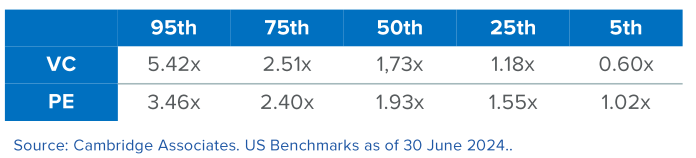

Investors committing to the VC industry for the first time need to have realistic expectations about the likely return profile for the asset class. The reality of venture capital is that the typical venture fund does not deliver the financial returns required to justify the risk and illiquidity of committing to VC. Figure 1 below shows the average quartile returns for VC vs private equity for 2000-2019 vintage funds.

Figure 1- 2000-2019 Average Percentile Returns (TVPI)

It is only by consistently accessing top-quartile VC funds that investors are able to capture the outperformance that the asset class has to offer. So how should family offices go about achieving this?

3. VC IS A POWER LAW INDUSTRY

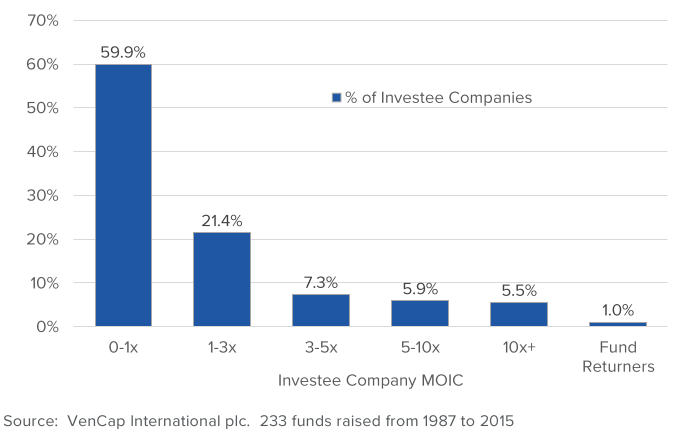

The return distribution of VC funds is driven by the power law nature of investing in startups. As can be seen in Figure 2 below, around 60% of early-stage, VC- backed companies ultimately fail to return cost back to their investors, with 27% of companies being complete write-offs.

Figure 2 – Early-Stage Investee Company Returns

While the majority of VC investments will lose money, there are a small number of companies formed each year that become hugely successful. These are the top 1% companies that deliver fund-returning outcomes and account for more than 50% of the total exit value created by the entire VC industry.

The power-law nature of venture capital means that building a direct co-investment programme is extremely challenging. The probability is that family offices are highly unlikely to have the skills and network necessary to identify and access top 1% companies. Instead, they are much more likely to co-invest in the 60% of deals that fail to return capital.

It is this ability to identify and access these top 1% companies early in their lives that is the greatest differentiator in the VC industry. It is also the single best way for VC funds to generate the top-quartile performance that LPs are targeting from their VC programme. The good news is that within VC there is a concentrated group of managers that have a proven ability to do exactly this.

4. PAST PERFORMANCE IS THE BEST GUIDE TO FUTURE PERFORMANCE

Venture capital is different from many asset classes in that the past performance of a VC firm is a fairly reliable guide to its future performance. Academic studies have shown that if a VC manager generated top- quartile performance from one of its funds, there is a 45% chance that the next fund will also be top quartile. Similarly, there is a 46% likelihood that a fund ranked in the bottom quartile will be followed by another bottom- quartile fund.

This means that if investors want to give themselves the best chance of selecting top-quartile funds, they need to wait until a manager’s track record is sufficiently developed to be a meaningful guide to future performance. In practice, this means avoiding emerging manager funds and only investing when it becomes clear that a manager has successfully accessed one or more top 1% companies.

The challenge with this strategy is not one of identifying managers, it becomes much more about the ability to access them. However, this is an area in which investors should not compromise. As we have seen in Figure 1, the difference between a top-quartile fund and the rest of the asset class is material. If investors can’t access the best managers, they should simply allocate their capital to other asset classes.

5. THE BEST COMPANIES TAKE TIME TO MATURE

VC performance typically takes time to develop with the losers usually emerging well before the winners. It can take 10-12 years for the best companies to go from being founded to an IPO. Given how few companies ultimately drive VC returns, the worst thing an LP can do is push their VC managers to sell their best companies prematurely in order to generate some DPI.

On the contrary, the best VCs are the ones that double down on their very best companies and allow them to compound over many years.

However, this does not mean that LPs must wait a decade or longer to see any returns from their VC programme. A properly constructed VC portfolio should be capable of generating distributions back to investors after 3-4 years and should become self- funding (ie distributions fund future capital calls) after 8- 9 years.

This is achieved by creating the appropriate stage mix within a portfolio. Depending on their risk/return and liquidity targets, investors should vary the balance of their portfolio between early-stage funds, later-stage/ VC growth funds and secondaries (ie buying LP positions in existing VC funds). The right portfolio mix has the advantage of reducing the typical VC J-Curve and accelerating liquidity, while still driving a strong money multiple (assuming access to the best managers).

6. SUMMARY

To build a VC programme that has the potential to capture the outperformance the best VC funds can generate, investors need to ensure that:

- They concentrate their portfolio on the very best managers with a proven ability of backing top 1% companies.

- They recognise that performance takes time to develop and have the patience to trust the best managers to deliver.

- They maintain a consistent annual investment pace and don’t try to time the market.

- They aren’t seduced by the promises and return forecasts of emerging managers with minimal or no track record to back them up.

VenCap has been following this strategy for many years, concentrating the majority of its capital into a small number of “Core Managers”. VenCap’s mature Core Manager investments (2000-2019 vintages) have generated a TVPI of 3.4x and an IRR of 21.5%.